A Taiwan ho incontrato divinità senza casa, suonato strumenti confuciani, ascoltato sciamani dialogare con i morti; ho chiesto auspici, visitato un meraviglioso museo dedicato alle religioni del mondo, mi sono perso in templi che parevano minuscoli e invece nascondevano stanze segrete, mi sono lasciato abbagliare da decorazioni rutilanti, eccessive, ingenue, sofisticate, kitsch. Una meta ricca di emozioni. Chi l’avrebbe mai detto!

In Taiwan, I met homeless deities, played Confucian instruments, listened to shamans talking to the dead, asked for omens, visited a wonderful museum of world religions, got lost in temples that seemed tiny but hid secret rooms, was dazzled by glittering, excessive, naive, sophisticated, kitschy decorations. A destination full of emotions. I would never have imagined it!

1 Le divinità ripudiate

Passi davanti a due grandi teche nella sala del National Taiwan Museum dedicata alla spiritualità a Taiwan e l’occhio ti cade su una serie di piccole statue di divinità sapientemente illuminate. Maschili e femminili, sorridenti e imbronciate, amichevoli o paurose, di origine taoista o buddista, loro ti guardano e tu le ricambi in modo distratto perché di statue come queste ne hai già viste tante nei templi cinesi. Poi l’occhio scivola quasi casualmente sulla didascalia accanto e allora scopri una storia davvero particolare, perchè quelle sono delle divinità ripudiate.

I cinesi sono grandi scommettitori, soliti affidare molte speranze alle lotterie. Per sostenere queste speranze si facevano un tempo costruire un simulacro della loro divinità favorita perché li aiutasse nella loro sorte. Pochi però erano i vincitori per cui le divinità tutelari dei perdenti venivano abbandonate davanti a templi, indegne di condividere il triste destino di chi non erano riuscite a sollevare. Che farne si chiesero allora i sacerdoti dei templi che di divinità simili sono già letteralmente ricoperti? Doniamole al Museo Nazionale e avranno nuova vita. E ora eccole qui solenni e splendenti, nella loro nuova casa pronte a donare fortuna anche solo con uno sguardo, grate per questa nuova vita a loro concessa.

1 Rejected gods

You are walking past two large display cases in the room of the National Taiwan Museum dedicated to spirituality in Taiwan, and your eye falls on a row of small, cleverly lit statues of deities. Male and female, smiling and sullen, friendly or fearful, Taoist or Buddhist in origin, they look at you and you absentmindedly look back at them because you have seen so many of these statues in Chinese temples. Then, almost casually, your eyes drift to the inscription next to them and you discover a very special story, for these are rejected deities.

The Chinese are great gamblers and used to place a lot of hope in the lottery. To support these hopes, they once had a simulacrum of their favourite deity built to help them with their fortunes. The winners, however, were few and far between, so the tutelary deities of the losers were left outside temples, unworthy to share the sad fate of those they had failed to raise. What to do with them, asked the priests of the temples, which were already literally covered with such deities? Donate them to the National Museum and they will have a new life. And now here they are, solemn and splendid, in their new home, ready to bestow good fortune with a glance, grateful for the new life they have been given.

2 Templi a sorpresa

Dovrebbe essere proprio qui, dice il navigatore, il Tempio di Tianhou. Sei su una strada trafficata nel quartiere più animato di Taipei, viene sera e le luci si accendono ma templi non se ne vedono. Poi noti delle impalcature schiacciate tra palazzi moderni, vedi gente che va e viene, qualche luce, e scoprì che quello è proprio l’ingresso del tempio che cercavi. Ti aspetti allora di entrare in una piccola sala, piena di statue e incensi come se ne incontrano a centinaia nelle vie di Taiwan, e ti domandi cosa possa avere questo posto di speciale per essere segnalato sulle guide. Entri nella prima sala, ti sembra che sia proprio come l’avevi immaginato; però il posto è bello, pieno di gente che prega e cerca auspici, in gran parte giovani. Poi vedi una freccia che indica una direzione, la segui ti pare di arrivare in un magazzino e stai per tornare indietro quando un ragazzo che regge un incenso ti sorpassa. Ci ripensi e lo segui deciso. Ed ecco una seconda sala, più grande e più ricca della prima. Ti senti soddisfatto di aver seguito il tuo istinto di cercatore. Poi vedi una scala che sale, una nuova freccia che indica verso l’alto e, visto che l’istinto non ti ha ingannato una volta, ci credi ancora ed eccoti in una terza sala sospesa, aperta su una terrazza, con altre statue e altri colori. Ma non è finita qui. C’è un altro piano, un altra visione. Sei dentro a una scatola a sorpresa, in uno stagno di colore circondato da grigi palazzi residenziali. Da un posto così è difficile staccarsi e ti abbandoni alle sensazioni, ai colori, ai profumi.

Di templi come questo ne ho scopertii altri a Taiwan: templi segreti, grandi e piccoli, animati o silenziosi e ogni volta ho rivissuto l’emozione provata quella sera varcando senza troppe aspettative il portale camuffato del tempio di Tianhou.

2 Temples of the Surprise

It should be right here, says the navigator, the Tianhou Temple. You are on a busy street in the busiest part of Taipei, the evening has come, and the lights are on, but there are no temples in sight. Then you notice some scaffolding squeezed between modern buildings, see people coming and going a few lights, and discover that this is indeed the entrance to the temple you are looking for. Then you expect to enter a small hall full of statues and incense, the kind you see by the hundreds in the streets of Taiwan, and you wonder what could be so special about this place as to be mentioned in the guidebooks. You enter the first hall and it seems to be just as you imagined it, but the place is beautiful, full of people praying and seeking blessings, mostly young people. Then you see an arrow pointing in one direction, you follow it, you think you are in a warehouse, and you are about to turn back when a boy with incense passes you. You think twice and decide to follow him. And here is a second hall, bigger and richer than the first.

You feel satisfied that you have followed your instincts as a seeker. Then you see a staircase leading up, another arrow pointing up, and since your instincts have never fooled you before, you believe it again and you find yourself in a third suspended hall, opening onto a terrace, with more statues and more colours. But that’s not all. There is another level, another vision. You are in a surprise box, in a pool of colour surrounded by grey apartment blocks. It is hard to get away from such a place and you surrender to the sensations, the colours, the smells.

I have discovered temples like this in Taiwan: secret temples, large and small, animated or silent, and each time I have relived the emotion I felt that evening when, without too many expectations, I crossed the camouflaged portal of the Tianhou Temple.

3 Educazione confuciana

Dei templi confuciani cinesi, cominciando da quello principale di Qufu, ricordavo una certa rigida assenza, dovuta al fatto che il culto vi è da tempo bandito e che sono stati trasformati in musei. Tributare il culto a un filosofo è al tempo stesso eccessivo e nobile, indice di una grande attenzione al pensiero, di una tendenza a innalzare l’umano al divino. Il pantheon cinese è pieno di generali, ingegneri, medici trasformati in divinità ma il ruolo di Confucio va oltre la semplice devozione. Qui si parla di formazione, di costruzione della persona, sostanzialmente di educazione, intesa nel modo più nobile del termine. I templi confuciani di Taiwan, in particolare quello della capitale, rinnovano non solo nella forma ma anche nella sostanza le virtù confuciane, cominciando dalla musica e dalla calligrafia. Un percorso attraverso le sale di un complesso splendidamente conservato porta a scoprire le arti confuciane, incluse quelle oggi meno praticabili, come il tito con l’arco e la corsa dei carri. Vedo una piccola processione che procede nel chiostro del tempio: si tratta di prove per una celebrazione futura. Da una stanza nell’angolo vengono musiche dai toni strani: si provano melodie antiche su strumenti desueti. Un abile calligrafo decora per te un cartocino rosso con ideogrammi evocativi. Confucianamente mi oriento sulla famiglia, virtù cardinale nel sistema di pensiero del Maestro Kong.

Mi emoziono quando nel tempio di Tainan scopro che passando le mani davanti alle sagome degli antichi strumenti del rito confuciano disegnate sulle pareti posso riprodurne i suoni. Il rispetto per Confucio è ancora diffuso in un paese che possiede un altissimo tasso di scolarità anche a livelli alti e che non se ne vergogna.

3 Confucian training

Of the Chinese Confucian temples, starting with the main one in Qufu, I recall a certain rigid absence, because worship has long been forbidden there and they have been turned into museums. To pay homage to a philosopher is both exaggerated and noble, a sign of great attention to thought, a tendency to elevate the human to the divine. The Chinese pantheon is full of generals, engineers and doctors turned into gods, but Confucius’ role goes beyond mere worship. It is about education, the construction of the person, education in the noblest sense of the word. Taiwan’s Confucian temples, especially the one in the capital, renew the Confucian virtues not only in form but also in substance, starting with music and calligraphy.

A walk through the halls of a beautifully preserved complex leads to the discovery of the Confucian arts, including those less practiced today, such as archery and chariot racing. I saw a small procession passing through the temple cloister: rehearsals for a future celebration. From a room in the corner came music in strange tones: ancient melodies being rehearsed on antiquated instruments. A skilled calligrapher is decorating a red card with evocative ideograms. I consciously orientated myself towards the family, a cardinal virtue in Master Kong’s system of thought.

In the Tainan temple, I was thrilled to discover that by passing my hands over the silhouettes of the ancient instruments of Confucian ritual painted on the walls, I could reproduce their sounds. Respect for Confucius is still widespread in a country that has a very high level of education, even at the highest levels, and is not ashamed of it.

4 Se un abaco ti osserva…

Tre caratteri di elegante calligrafia campeggiano all’ingresso del Dio della Città di Tainan. Significano (me lo dicono ovviamente) “Alla fine eccoti qui”. Effettivamente ora ci sono e il luogo mi piace assai, trattandosi di uno dei templi più antichi dell’isola (fu fondato nel 1699). Se però non vedessi accanto alla scritta un grande abaco potrei essere più tranquillo riguardo al suo senso. A Pechino ho già visto un utensile simile in un tempio di spaventose presenze e so che cosa significa: adesso possiamo procedere alla conta dei tuoi peccati e delle tue buone azioni e poi decideremo che farcene della tua anima.

Come non sentirsi inquieto davanti a un’azione così proditoria? Sono venuto qui ad ammirare, non dico a venerare perché mentirei, la elegante statua del Duca Weiling che di Tainan è lo spirito protettore e ora rischio un giudizio sommario?

Sfoggiando un distaccato atteggiamento, poiché la mia provenienza giustifica l’ignoranza di certi codici, mi aggiro così indifferente ammirando eleganti sculture, statue di personaggi bizzarri che sono, come spesso accade in Cina, un po’ taoisti e un po’ buddisti. Ma, appena alzo lo sguardo ecco l’abaco che incombe, così prendo dignitosamente una via di fuga. Non è il momento di pensare a giudizi e trapassi. Sarà proprio così?

4 If the abacus is watching…

Three characters of elegant calligraphy stand at the entrance to the Tainan City God. They mean (they tell me, of course) ‘Here you are at last’. Now I am indeed there and I like the place very much, as it is one of the oldest temples on the island (it was founded in 1699). However, if I did not see a large abacus next to the inscription, I might be more relaxed about its meaning. I have seen a similar tool in Beijing, in a temple of terrifying presences, and I know what it means: now we can count our sins and good deeds, and then we will decide what to do with our souls.

How can one not feel uneasy at such an astonishing act? I came here to admire, I don’t say worship, because that would be a lie, the elegant statue of Duke Weiling, the patron saint of Tainan, and now I risk summary judgment?

With a detached attitude, as my origin justifies my ignorance of certain codes, I wandered so indifferently, admiring elegant sculptures, and statues of bizarre characters that, as is often the case in China, are a little bit Taoist and a little bit Buddhist. But as soon as I look up, the abacus looms, so I make a dignified escape. This is not the time to think about judgments and passages. Is it really going to be like this?

4 Parlare con i defunti

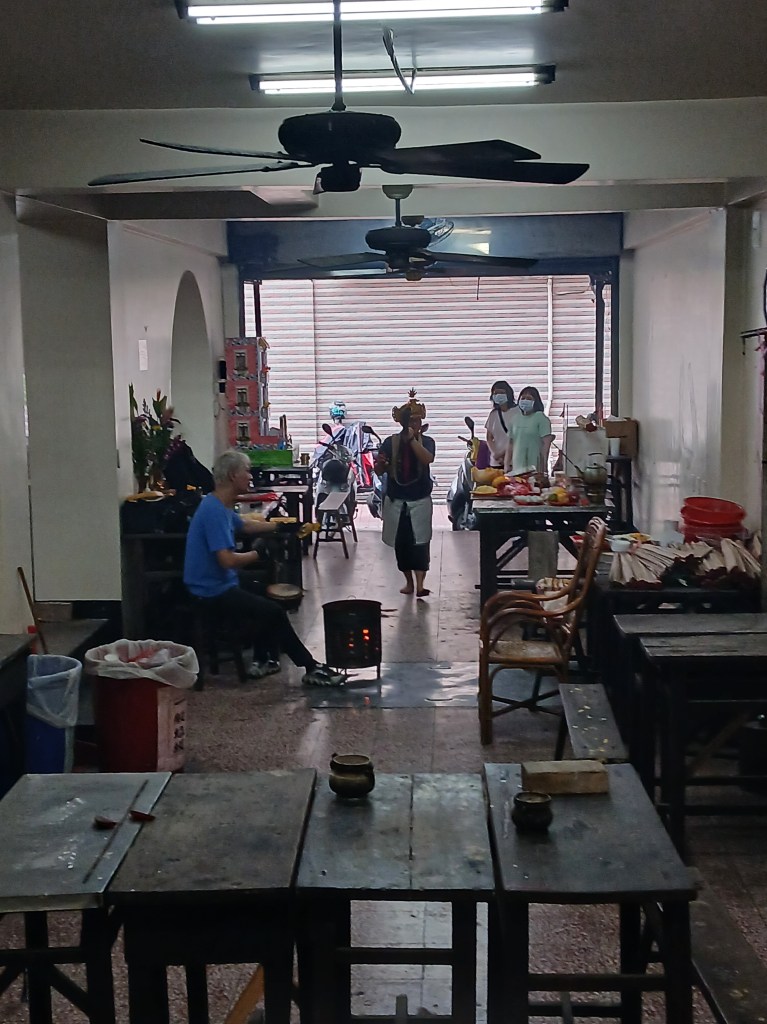

Il vicolo che parte proprio davanti al tempio del Dio della Città è uno dei tanti che intersecano le vie porticate della antica Tainan, la prima capitale dell’isola di Formosa, come un tempo era conosciuta Taiwan. Ci sono vasi di fiori davanti a ogni porta, tutto è pulito e immacolato. Poi arrivo davanti ad alcune bancarelle: c’è un piccolo mercato nascosto sotto dei portici da cui emanano i soliti intensi odori di cibo taiwanese. Avverto però uno strano rumore in sottofondo, un battere ritmato di cembali, in cui si inserisce il suono di un corno, sorprendente e inquietante in quel luogo e in quel contesto. Tutto pare provenire da un paio di locali alla fine del vicolo che sembrano due garage, in cui su tavoli sgangherati compaiono curiosi modellini di case, persone, oggetti.

Uomini e donne che indossano degli strani cappelli camminano tra i tavoli producendo quei suoni, a cui si è aggiunto ora un tamburello, e ripetendo delle specie di litanie. Ci sono bracieri dove si bruciano effigi, i soliti incensi, persone che dopo aver parlato con uno di questi strani personaggi, chinano il capo davanti alle sue giaculatorie e iniziano a seguirlo in un percorso che comprende l’adiacente tempio Dongyue. Questo è il luogo dedicato alla comunicazione tra il mondo presente e quello dell’aldilà e che quei personaggi bizzarri altro non sono che sciamani che invocano, ovviamente a pagamento, la presenza di anime defunte richieste dai parenti.

La religiosità popolare cinese è basata sulla credenza che esista un vero e proprio mondo parallello dove le anime vanno a sostare in attesa di future reincarnazioni, un mondo dove tutto quello che serviva in questo, compresi gli oggetti più futili, può essere riprodotto ed usato. Da qui la presenza di soldi, oggetti, generi di lusso in carta che vengono consacrati e poi bruciati così che il fumo li convogli verso il cielo.

Mi rintano dietro un muro divisorio e approfittando di una finestra semi aperta spio i riti che avvengono nei due ambienti piuttosto squallidi dove sostano gli sciamani. Dovrei provare un brivido e invece mi sento un pochino stranito. Penso solo, in modo del tutto pratico, che un approccio tanto importante avrebbe meritato un ambiente migliore.

4 Talking to the dead

The alleyway that starts just outside the temple of the city god is one of many that intersect the arcaded streets of ancient Tainan, the first capital of Formosa Island, as Taiwan was once known. There are flower pots outside every door, everything is clean and immaculate. Then I came to some stalls: a small market hidden under arcades, with the usual intense smells of Taiwanese food. In the background, however, I heard a strange noise, a rhythmic beating of cymbals interspersed with the sound of a horn, surprising and disturbing in this place and context. Everything seems to be coming from a couple of rooms at the end of the alley, which look like two garages, where strange models of houses, people, and objects appear on rickety tables.

Men and women in strange hats walk among the tables, making those noises, now joined by a tambourine, and repeating some sort of litany. There are braziers where effigies are burned, the usual incense, and people who, after talking to one of these strange figures, bow their heads to his ejaculations and begin to follow him along a path that includes the adjacent Dongyue Temple. This is the place dedicated to communication between the present world and the afterlife, and these bizarre characters are none other than shamans who, obviously for a fee, invoke the presence of deceased souls requested by relatives.

Chinese popular religion is based on the belief that there is a real parallel world where souls rest while awaiting future reincarnations, a world where everything needed in this world, including the most useless objects, can be reproduced and used. Hence the presence of money, objects, and paper luxuries that are consecrated and then burned so that the smoke carries them to heaven.

I hide behind a partition and take advantage of a half-open window to spy on the rituals taking place in the two rather dingy rooms where the shamans live. I should feel excited, but instead, I feel a little strange. I just think, in a very practical way, that such an important approach would have deserved a better setting.

6 Par condicio underground

Del tunnel che dal piazzale del tempio Guandu si inoltra sotto la collina avevo sentito parlare come di un luogo particolare e unico a Taiwan. Immaginarsi una galleria decorata con statue buddiste è un esercizio divertente e l’immaginazione ricorre alle più bizzarre visioni. Sapendo poi che questo percorso è stato ricavato da uno dei tanti rifugi sotterranei creati per proteggere da guerre passate o da tifoni presenti l’aspettativa è ancora più alta. L’impatto però non è così entusiasmante: statue di arhat e santi buddisti chiuse in bacheche illuminate da fredde luci al neon segnano le tappe del percorso. Dopo un centinaio di metri mi trovo alla presenza di una spettacolare statua dorata di Avalokitesvara dalle mille braccia, simbolo concreto della misericordia nel buddsimo di scuola mahayana, riemergendo sul versante opposto della collina dove una terrazza si apre sul sottostante fiume Tamsui. Sebbene qualche devoto si fermi davanti a ogni vetrina il tragitto mi pare un po’ gelido e senza pathos. Arrivato al terrazzo, guardo il fiume, mi inchino alla sempre inquietante Avalokitesvara e mi avvio sulla via del ritorno pensando che l’esperienza tutto sommato non valeva il viaggio. Per fortuna il grande e animato tempio Guandu è invece uno dei più attvi, frequentati e vivaci dell’isola: altari ovunque, canti di sacerdoti per cerimonie private, sutra recitati da donne in tonaca marrone, via vai di incensi. Come sempre divinità taoiste e buddiste convivono serenamente pur occupando sale diverse e non mi stupisco più di tanto scoprendo che anche sotto terra viene rispettata la par condicio cinese delle fedi. Un secondo tunnel parallelo consacrato al dio taoista della prosperità corre quasi parallello a quello buddista e, al termine invece della dea dorata, mi ritrovo ad ammiraare il classico simbolo dello yin & yang, il sobrio e ammiccante logo taoista ormai entrato nell’iconografia universale, associato, chissà perché al concetto di benessere e beauty. Qui di beauty, nel senso occidentale del termine, ce n’è però davvero poca, compensata però da una vivida e contagiosa religiosità. Possiamo definirla una forma di benessere? Nel senso cinese del termine direi proprio di sì.

6 Par condicio underground

I had heard that the tunnel running under the hill from the forecourt of Guandu Temple was a special and unique place in Taiwan. Imagining a tunnel decorated with Buddhist statues is an amusing exercise, and the imagination reaches for the most bizarre visions. Add to this the knowledge that this path has been carved out of one of the many underground shelters built to protect against past wars or present typhoons, and the anticipation is even greater. But what I find is not so exciting: statues of arhats and Buddhist saints in display cases lit by cold neon lights mark the stages of the path. After a hundred metres or so, a spectacular golden statue of the thousand-armed Avalokitesvara, a concrete symbol of mercy in Mahayana Buddhism, reappears on the opposite side of the hill, where a terrace opens out onto the Tamsui River below.

Although a few devotees stop in front of each shop window, the walk seems a little icy and devoid of pathos. Arriving at the terrace, I gazed out over the river, bowed to the ever-eerie Avalokitesvara, and made my way back, thinking that the experience was not worth the trip. Fortunately, the large and bustling Guandu temple is instead one of the most attentive, busy, and lively on the island: altars everywhere, priests chanting for private ceremonies, sutras recited by women in brown cassocks, the smell of incense. As always, Taoist and Buddhist deities coexist peacefully, though they occupy different halls, and I am not too surprised to discover that the Chinese par condicio of faith is respected even underground. A second parallel tunnel, dedicated to the Taoist god of prosperity, runs almost parallel to the Buddhist one, and at the end, instead of the golden goddess, I find myself admiring the classic symbol of Yin & Yang, the sober and tongue-in-cheek Taoist logo that has now entered universal iconography, associated, who knows why, with the concept of well-being and beauty. Here, however, there is very little beauty, in the Western sense of the word, but it is compensated for by a lively and contagious religiousness. Can we call it a form of well-being? In the Chinese sense, I would say yes.

7 Lo stagno del loto

Lo Stagno del Loto di Kaoshiung è uno dei luoghi più bizzarri e unici di Taiwan. Per questo, sfidando un incombente temporale che fortunatamente non arriverà mai, lo raggiungo la mattina di un giorno feriale quando l’affluenza è minore e permette una visita più tranquilla. Lo stagno è in realtà un lago, neppure tanto piccolo, che si può facilmente percorrere seguendo una comoda e ben tenuta pista ciclopedonale che tocca tutti i templi che lo circondano. Putroppo le due pagode dedicate rispettivamente alla Tigre e al Dragone che lo hanno reso famoso sono in restauro e quindi mi perdo l’effetto delle colossali e pacchiane statue dei due animali eponimi che si allungano verso la riva con un effetto che noi giudicheremmo più da parco dei divertimenti che da luogo sacro.

Il mood kitch prosegue nelle tappe successive con passerelle che si protendono nel lago con percorsi sinuosi tra dragoni dentro cui si può camminare e statue gigantesche. Sulla terraferma a ogni statua corrisponde un tempio dove si ritrova la rutilante e ed eccessiva estetica templare tipica della Cina Meridionale con musici taoisti, percorsi segreti e sale sospese. Unica, notevole eccezione il grandioso Tempio di Confucio, recentemente tirato a lustro, che spicca per la sua elegante estetica settentrionale stile Città Proibita, estetica che, nella sua maestosa e misurata eleganza, pare qui abbastanza anomala.

7 The Lotus Pond

The Lotus Pond in Kaohsiung is one of the most bizarre and unique places in Taiwan. That is why, braving a threatening thunderstorm that fortunately never comes, I arrive on a weekday morning when the crowds are fewer and a quieter visit is possible. The pond is actually a lake, not that small, which can be easily crossed by following a comfortable and well-maintained cycle path that touches all the surrounding temples. Unfortunately, the two pagodas dedicated to the Tiger and the Dragon that made it famous are being restored, so I missed the effect of the colossal and gaudy statues of the two eponymous animals stretching out towards the shore with an effect that we would judge more as an amusement park than a sacred place.

The kitschy mood continues in the later stages, with footbridges stretching out into the lake, winding paths between dragons you can walk inside, and gigantic statues. On land, each statue corresponds to a temple, where you will find the glittering and excessive temple aesthetic typical of southern China, with Taoist musicians, secret passageways, and suspended halls. The only notable exception is the grandiose, recently refurbished Confucius Temple, which has the elegant, Forbidden City-style aesthetic of the north, an aesthetic that seems rather anomalous here in its majestic and understated elegance.

8 Innamorati di Mazupo, la Madre Celeste

Se andate a Taiwan, nel Fujian, a Hong Kong, a Kuala Lumpur o a Singapore non potrete fare a meno di imbattervi in Mazu, alias Tianhou alias Mazupo come la chiamano affettuosamente qui.

La storia di Mazu, la divinità più amata nella Cina Meridionale e nella diaspora cinese dei mari del sud, è abbastanza emblematica della tradizione cinese di deificare personaggi storici e reali. Si chiamava Lin Mo, era nata in un villaggio del Fujian nel 960 d.C. e nella sua breve vita di soli 28 anni dovette compiere atti di notevole virtù, specialmente rivolti alla tutela dei marinai, per divenire nel tempo la patrona assoluta di tutto ciò che in area cinese è legato al mare.

La Mazu, che ora guardo sugli altari taiwanesi, una robusta signora che indossa un copricapo quadrato da cui scendono file di perline, mi appare però troppo ieratica per possedere quell’empatia comune alle Regine del Cielo di altre religioni. Ma è meglio non esternare ad alta voce questi pensieri: dicono infatti che i due demoni che la affiancano siano follemente innamorati di lei e la proteggano contro ogni insidia. “Orecchie che Ascoltano il Vento” pare osservarmi attento mentre “Occhi che Scrutano per Mille Miglia” sta corrugando una palpebra. Forse sono solo stanchi di ascoltare tempeste (una è appena passata e un’altra arriverà tra poco) o di cercare una vela che appare all’orizzonte da dove oggi potrebbero profilarsi ben diverse e più inquietanti minacce. Di tuttto ciò le migliaia di persone che ogni giorno, in ogni villaggio di Taiwan, visitano un santuario dell’amica Mazupo paiono non curarsi: ben altro hanno da chiedere alla dea: mi sposerò? Vincerò alla lotteria? Lui mi ama? Demoni protettori siete pregati di rispettare la privacy!

8 In love with Mazupo, the Heavenly Mother

If you go to Taiwan, Fujian, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, or Singapore, you are bound to come across Mazu, Tianhou, or Mazupo, as she is affectionately known.

The story of Mazu, the most popular deity in southern China and the Chinese diaspora in the South Seas, is emblematic of the Chinese tradition of deifying historical and royal figures. Her name was Lin Mo, she was born in a village in Fujian in 960 A.D., and in her short life of only 28 years, she had to perform acts of remarkable virtue, especially for the protection of sailors, to become the absolute patron saint of everything related to the sea in Chinese territory.

The Mazu I see today on Taiwanese altars, a robust woman with a square headdress from which rows of pearls descend, seems to me too hieratic to possess the empathy common to the celestial queens of other religions. But it is better not to say these thoughts aloud: they say that the two demons flanking her are madly in love with her and protect her against all odds.

‘Ears that listen to the wind’ seem to be watching me intently, while ‘Eyes that see a thousand miles’ is blinking. Perhaps they are simply tired of listening to storms (one has just passed and another is about to arrive), or of searching for a sail that appears on the horizon, from where far different and more ominous threats may be looming today. None of this seems to matter to the thousands of people who visit a shrine to their friend Mazupo every day in every village in Taiwan: they have much more important things to ask the goddess: will I get married? Will I win the lottery? Does he love me? Demon guardians, please respect privacy!

9 Quel persistente toc toc sul pavimento

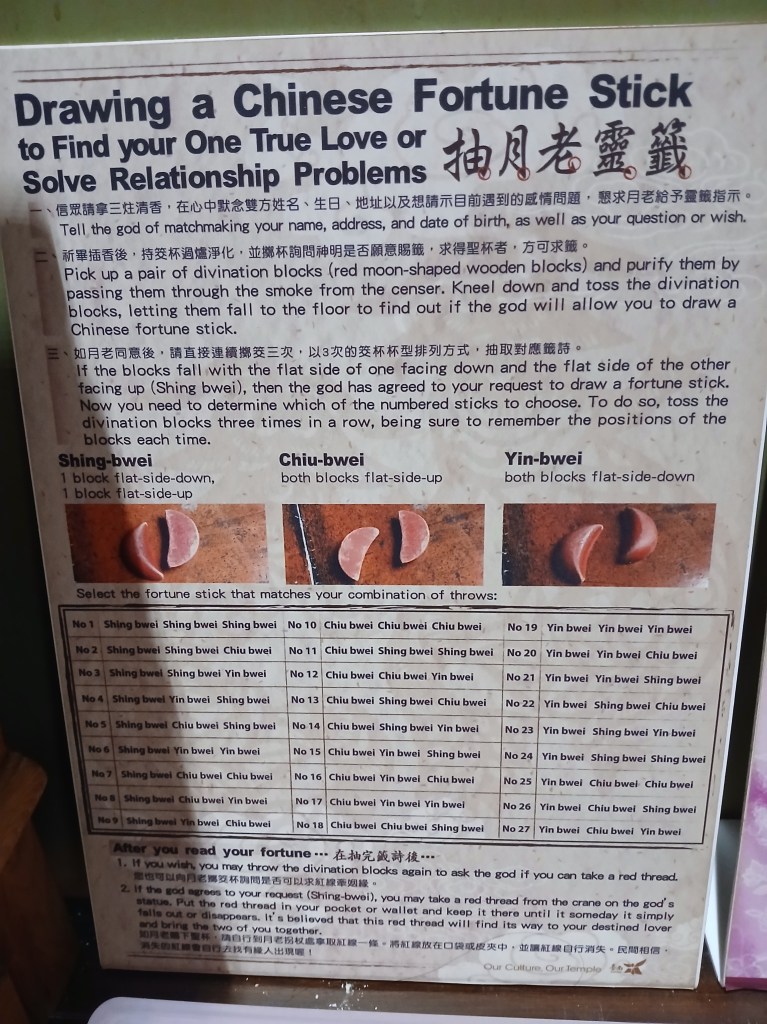

Toc toc, toc toc: sei in un tempio e questo suono ti accompagna. Prima pensi che a qualcuno sia caduto qualcosa poi però, visto che il suono si ripete, ti chiedi se questo qualcuno sia maldestro o distratto o se stia succedendo in realtà qualcosa di diverso. Allora ti guardi attorno e davanti a uno qualsiasi degli altari del tempio vedi una figura inginocchiata che lancia sul pavimento un paio di oggetti di legno, spesso dipinti di rosso, che ricordano spicchi di arancia. In realtà, guardandoli bene, scopri che ce ne sono ovunque di questi oggetti, riposti in cesti o vassoi. Allora ne prendi uno in mano e vedi che ha due facce diverse: una è piatta, l’altra è convessa. Provi a lasciarle cadere a terra e ti appaiono due facce uguali. Sono entrambe piatte. Scoprirò poi di essere stato fortunato. Male sarebbe stato se fossero state entrambe convesse. Ci sarebbe stato invece da discutere se l’una e l’altra fossero state diverse. Scoprirò anche che purtroppo prima di lanciarle non ho formulato alcuna domanda e quindi non saprò mai a cosa il dio aveva dato il suo parere favorevole.

9 That persistent knocking on the floor

Knock, knock, knock: you are in a temple and this sound accompanies you. At first, you think that someone has dropped something, but then, as the sound repeats, you wonder if the person is clumsy or distracted, or if something else is happening. Then you look around, and in front of one of the temple’s altars, you see a kneeling figure throwing some wooden objects, often painted red, that resemble orange segments, onto the floor. In fact, if you look closely, you will discover that there are such objects everywhere, stored in baskets or trays. Then you pick one up and see that it has two different faces: one is flat, and the other is convex. You try to drop it on the floor and two identical faces appear. They are both flat. I found out later that I was lucky. It would have been bad if both had been convex. Instead, there would have been arguments if one had been different from the other. I will also discover that, unfortunately, I did not formulate any questions before casting, so I will never know what the god gave his favourable opinion on.

Shakerare i bastoncini votivi è un’operazione più familiare. Ne posseggo anch’io un set e in certe occassioni mi affido alle risposte oracolari contenute in un libricino scritto in un inglese arcaico e criptico. Nei templi invece le risposte sono spesso contenute in eleganti armadietti divisi in piccoli cassetti ciascuno segnato da un numero corrispondente a quello del bastoncino. Purtroppo sono solo in cinese e quindi neppure ci provo. Mi dicono che in realtà la divinazione più perfetta è quella che nasce dalla combinazione di lancio degli “spicchi d’arancia” e estrazione di un bastoncino ma le regole sono talmente complesse che neppure ci provo a spiegarle!

Shaking votive sticks is a more familiar operation. I have a set myself and on certain occasions rely on the oracular answers contained in a small booklet written in archaic and cryptic English. In temples, on the other hand, the answers are often kept in elegant cabinets divided into small drawers, each marked with a number corresponding to that of the stick. Unfortunately, they’re only in Chinese, so I don’t even try. They tell me that the most perfect divination is actually the one that comes from the combination of throwing ‘orange segments’ and drawing a stick, but the rules are so complex that I don’t even try to explain them!

Quello che invece faccio perché non richiede alcuna conoscenza superiore è acquistare un cartocino a uno dei banchetti che si trovano in ogni tempio. Ci scrivo il nome, il cognome e l’ambito in cui vorrei che si esaudisse il mio desiderio (salute, ricchezza, famiglia, amore…) e lo appendo a un albero del tempio Zhinan che domina la città di Taipei con le sue belle terrazze.

Da una sala vengono voci di preghiere: un sacerdote taoista bardato con tunica e cappello liturgico presenta richieste a una fiamma mentre due accoliti gli fanno eco in una preghiera responsoriale di un certo fascino. La scena è accentuata dalla luce calante che esalta fiammelle e migliaia di piccole lampade votive che sbucano ovunque. Intanto il vento agita la mia richiesta, e sa già che una, quella di essere lì in quel momento ad ascoltare quel canto, è stata esaudita!

What I do instead, because it requires no higher knowledge, is to buy a card at one of the banquets that can be found at each temple. I write my name, surname, and the area in which I want my wish to be granted (health, wealth, family, love…) and hang it on a tree in the Zhinan Temple, which overlooks the city of Taipei with its beautiful terraces.

The voices of prayer come from a room: a Taoist priest, dressed in a tunic and liturgical hat, makes requests to a flame, while two acolytes join him in a responsorial prayer of a certain charm. The scene is accentuated by the fading light, which intensifies the flames, and by the thousands of small votive lamps that appear everywhere. Meanwhile, the wind is stirring up my wish, and it already knows that my wish to be there at this moment to hear this song has been granted!

10 Religioni di tutto il mondo unitevi!

Per addentrarsi tra vie tranquille e popolari di New Taipei, la contro-metropoli che avvolge la capitale di Taiwan ci vuole un buon motivo e io ce l’ho. Sono qui per visitare il Museum of World Religions uno dei pochi al mondo dedicati esclusivamente alle tematiche religiose. Perché l’abbiano voluto costruire proprio in questo sobborgo anonimo è un gran mistero, sembra quasi che il messaggio sia: se mi conosci mi cercherai ma io non farò nulla per farmi notare. E ci riesce benissimo a non farsi notare visto che si trova quasi mimetizzato agli ultimi due piani di uno stretto palazzo infilato tra altri più massicci e che solo un discreto totem sistemato davanti all’ingresso ne annuncia la presenza.

Quello che si scorpre all’interno però smentisce l’immagine un po’ sottotraccia dell’approccio. La presentazione è fin dall’inizio, dove si incontra una grande parete da cui scende acqua, molto suggestiva, tecnologica e concettuale. Per saperne di più andate a visitare il sito del museo che vi racconterà come e perché il museo sia nato e come sia articolato. Io mi limito a segnalare due esperienze: quella della grande sala delle religioni in cui alle pareti si sussegguono teche con oggetti rituali delle principali religioni del mondo mentre la parte centrale è occupata da modelli in scala dei principali luoghi di culto e quella della sottostante sala che racconta in modo trasversale le fasi della vita dalla nascita alla morte viste dalle diverse religioni. Qui sono stato catturato dalla Meditation Hall dove seduto su una pedana ho potuto ascoltare e condividere preghiere e formule sacre recitate da fedeli di ogni religione, dai mantra al rosario. Tutto nel museo è ordinato, elegante, ben illuminato, tecnologicamente evoluto, con filmati, tavole interattive e tutto quanto si richiede a un museo contemporaneo. Persino il bar è luminoso ed elegantemente minimal. E tutto è ovviamente presentato anche in inglese. Da non perdere.

10 Religions of the World – Unite!

Why they chose to build it in this anonymous suburb is a great mystery; it almost seems as if the message is: if you know me, you will look for me, but I will do nothing to attract attention. And it does a very good job of not being noticed, being almost camouflaged on the top two floors of a narrow building sandwiched between other, more massive ones, with only a discreet totem placed in front of the entrance announcing its presence.

What you see inside, however, belies the somewhat underwhelming image of the approach. Right from the start, the presentation is striking, technological, and conceptual, with a large wall from which water gushes. If you want to know more, visit the museum’s website, where you can find out how and why it was created and how it is organized.

I will confine myself to two experiences: that of the Great Hall of Religions, where the walls are lined with display cases of ritual objects from the world’s major religions, while the central part is occupied by scale models of the main places of worship; and that of the hall below, which tells of the stages of life, from birth to death, from the point of view of the different religions. Here I was captivated by the Meditation Hall, where, sitting on a platform, I was able to listen to and participate in prayers and sacred formulae recited by believers of all faiths, from mantras to the rosary. Everything in the museum is neat, elegant, well-lit, technologically advanced, with films, interactive panels, and everything else you would expect from a modern museum. Even the bar is bright and elegantly minimalist. And, of course, everything is in English. Not to be missed.